19 Mar Don’t call me Fuzzy

Before Slavery

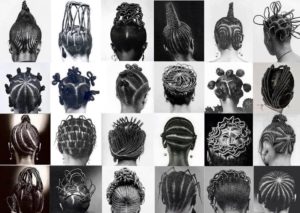

In the fifteenth century, African hair was an unmistakable type of communication. African hair talked about age, marital status, ethnic character, religion, riches, and social status. For example, in the Wolof clan of Senegal, young ladies would shave a part of their hair to tell the unhitched males that they were single and ready for the picking.

Africans knew their hair was excellent. They would invest hours washing, brushing, and oiling their hair to guarantee it stayed sound. Africans used to utilize expand brushes, brushes, and trimmings like cowrie shells to feature the magnificence of their hair.

There are two primary misguided judgments that come with African hair.

The main misinterpretation is that normal hair is “messy”. The second is that natural hair does/doesn’t grow (subsequently the fixation on hair length, hair extensions and dreadlocks).

Numerous dark ladies and men who wear weaves and lock their hair will clarify their decision by either saying that their common hair is “unmanageable” or that characteristic hair is “grimy”. This is a standout amongst the most persevering generalizations about dark hair. Individuals will even refer to the “episodic” confirmation that Bob Marley’s fears had 47 distinct kinds of lice when he passed on. These are urban legends of the most noticeably awful kind since they propagate the generalization that exclusive dark hair pulls in lice, and other vermin, which is just experimentally false.

Bob Marley’s hair was the subject of a few myths. Verifiably, the myth originates from pictures of the mockingly named “fluffy wuzzy” that British troopers who were battling Sudanese guerillas in the Mahdist War sent home. This war, from 1881-1899, promoted the picture of the wild Afros that individuals now envision when they consider dark hair. These pictures are deceiving for the basic reason that they propose these Sudanese fighters did not “dress” their hair or wash it, since in the pictures it regularly looks unkempt. Nothing could be further from reality. Over the African mainland, methods for dressing hair were as fluctuated as the hairdos that they delivered.

In Africa our hair is synonymous to crowns, and the intricate styles are worn with pride.

to crowns, and the intricate styles are worn with pride.